I’ve always liked the concept of litotes (pronounced lie-toe-tees) . As a literary device, litotes is the practice of negating a negative, thus creating a positive. For example, you might say you “wouldn’t say no” to dessert, or that a romantic interest is “not bad looking.” Litotes engage your conversation partner, inviting them to solve your mini-riddle.

The thing is, I’m tired of calling myself chronically ill. I’ve long been searching for better language to describe the medical twist of fate that disrupts millions of lives. I’ve tried out “working illness,” since parents and caregivers with chronic illnesses are the teachers, doctors, engineers, baristas, and stay-at-home parents who make the wheels of capit — err, society, turn. As for litotes, I suppose I’m a not infrequently hospitalized mother.

When my chronic illness, Multiple Sclerosis, became suddenly and intensely aggressive, I could no longer hide behind a sunny disposition or dedication to my career. As the not unstressful 2020 school year came to a close, I was hit hard by a rare, stroke-mimicking MS flare. To this day, I struggle with debilitating chronic pain, appetite disfunction, fatigue, spasticity, cognitive fog, and depression. Since the flare affected my dominant left side, I struggle to fill out simple forms. When this happens, I feel inadequate, because every parent knows that child-rearing is at least 10% filling out forms.

And so I submit for review this non-exhaustive list of tips I learned the hard way, so you don’t have to. I hope it helps — at least I hope it doesn’t hurt.

1. Do your best, not the most. Other parents can make a full dinner from scratch each night. Sometimes other parents have cool jobs, or make lots of money. Still more parents take their families on spur of the moment vacations with the Instagrams to prove it. As Olivia Rodrigo says, other parents are everything we’re insecure about. But you’re not other parents. Instead of of chopping down a Christmas tree and instagramming the *magic*, you can break out your dazzling white tree with multicolor lights built in! We got ours from Walmart and plan to keep it for years to come. Your unsteady hand may not light a menorah, but that’s an opportunity for your children to try. My point is, your kids love you for who you are and the safety and security they feel when you are around — other parents simply wouldn’t do.

2. The body, it turns out, really does keep the score. Don’t let your illness sink three-pointers without a strong defense of rest, healthy boundaries, and restorative laughter with your kid(s). I’m glad my body was able to finally get through to my mind and show me that the pace of my life was unsustainable. I wouldn’t choose paralysis or pain but, in retrospect, the situation forced me to accept that I was pushing too hard. I am also a mother, an educator, a creator, and a human being with a story to tell. And that’s enough. You are enough. And to your children, you’re everything.

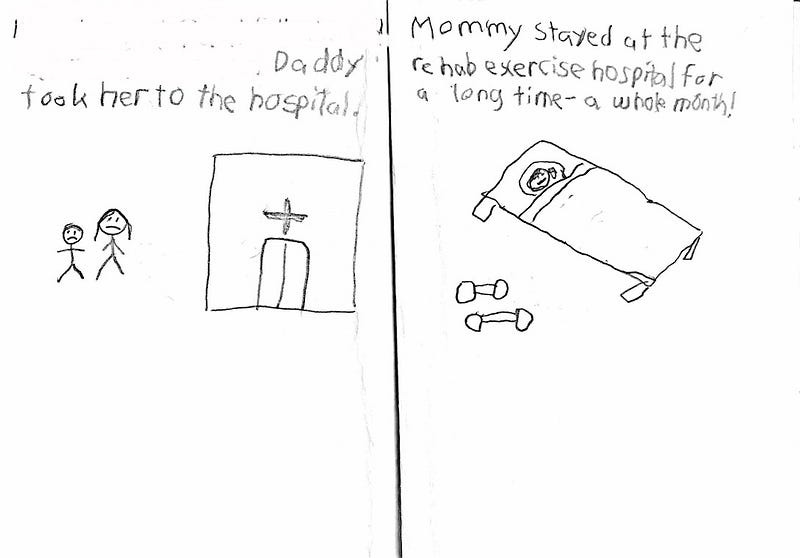

3. Social stories can help your child process your absence. During my longest hospital stay, my kids were 4 and 6 years old. I had never been away from my youngest for more that a night. I struggled with feeling that I had abandoned them; that I was their living Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE). When my inpatient therapist told me about social stories, I was reaching for my practice pad before she was finished. Social stories are simple narratives (with pictures for younger kids) that present the facts of what happened without too much emotion attached. Children can read, or “read” these stories over and over to help gain a footing. My teacher instincts kicked in, and I realized that I could help them through this time.

4. Tell somebody at work about your condition. If you work outside the home, even if you don’t feel comfortable disclosing your illness to HR, find a trusted and trustworthy colleague. They don’t need to be your best friend, but work life is so much easier when you can share your struggles with somebody who understands the specific demands of your workplace. It also helps to have a colleague to reach out to when you’re hospitalized! If you’re a stay at home parent, having a neighbor or friend to chat with can help.

Sarcasm without a hint of optimism is poison. Don’t drink it.

Rule 4. Avoid the grumblers. There will always be somebody whose self worth rests upon their ability to re-enact a meeting that “could’ve been an email.” These same self-identifying sarcastic people will read aloud an email they’ve deemed both hilarious and awful. Avoid these conversations when possible because sarcasm without a hint of optimism is poison. Don’t drink it. If you struggle just to get through the day, protecting your mental energy at work is essential for happiness at home. When I was working, my kids generally understood when I was spent from a long day, but when I brought home negative energy, they could feel it, too.

Rule 5. Beware Wellness Culture. Nobody asked all the bosses to take a workshop that said deep breathing, yoga, and hydration are the keys to a successful and happy workforce, yet here we are. Probably the most glaring example of Big Wellness’ hold on culture is Amazon’s AmaZen program. Features include video read-along mindfulness breaks at workstations and an eerie “mindful wellness room” the size of a refrigerator. But Bezos is an easy target — many workplaces that already have positive and strong cultures have jumped on the wellness bandwagon. As a disabled worker, I feel comfortable saying that wellness is for the well, and chronically ill workers struggle at workplaces that are wellness-forward, but not truly inclusive. What good is a reminder to “get up and move!” to those of us with motor disabilities or chronic fatigue?

Rule 6. Embrace Your Wellness Toolkit. I know, I just told you to beware! However, the only way I have been able to move forward after my complex brain injury has been through some variation of wellness practices. I generally follow stroke and TBI techniques, but every chronic illness is different. Breath-work, physical therapy, meditation, visualization, and stretching are just some of the techniques I use to get through a week. The thing is, the practices I use are highly specific to my condition. Beyond my physical limitations, I also suffer from brain fog, vertigo, emotional disregulation, and debilitating chronic pain. It’s taken over two years to find, vet, and make time for the practices that truly help me on a day to day basis. But when you find the practices that work for you, hold on tight.

Erin Ryan Heyneman is a disabled parent, educator, creator, and member of her city’s Commission on Disability.

Socials: erinryanhey

Website